Nov 21, 2020: Climate emergency action plan approved

Vancouver is going it alone in the fight against climate change, becoming the first municipality in British Columbia to approve an climate emergency plan.

On November 17, 2020, City Council set in motion its Climate Emergency Action Plan (CEAP) that calls for cutting 2007 carbon emission levels from buildings by half, and for two-thirds of all trips in the city to be made by foot, bike or transit by 2030.

Proponents say the CEAP is more ambitious than the province’s CleanBC action plan because it views the need for climate actions as an “emergency.” Take space and water heating in new buildings, for one example. CEAP requires all new buildings to transition from natural gas or other fossil fuel to green alternatives by 2021 — more than a decade sooner than the province’s target of 2040.

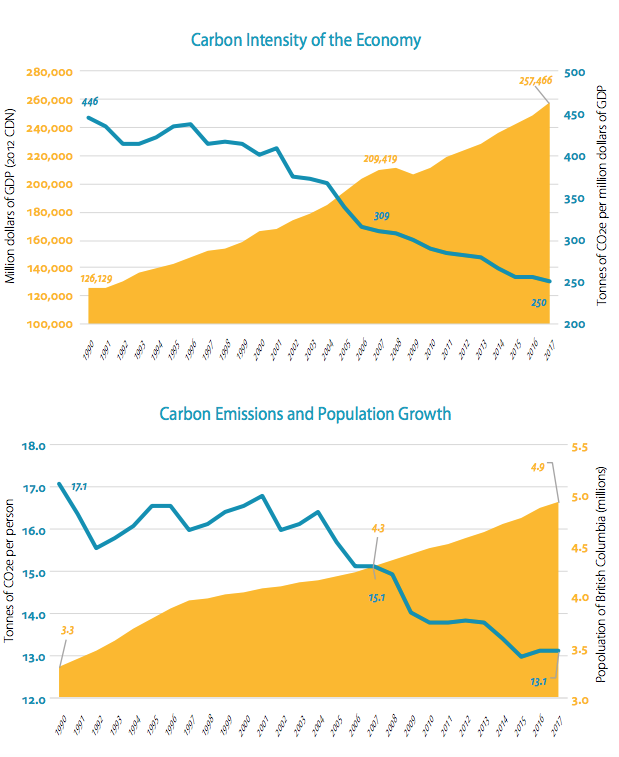

Critics, however, question the need for such urgent action, particularly since overall carbon emissions in the province have actually declined since 1990 levels as the graphs below show:

Graphs: Province of BC, 2019

Beginning in the New Year, broader public input will be sought, say staff, as the details of the CEAP are hammered out. But for now, there are many issues that remain unknown, such as the implications for those living on fixed incomes, and seniors — the fastest-growing population in the city (from 1996 to 2016, the absolute number of seniors in Vancouver increased by 46 per cent, double the rate of growth in the overall population).

Implementing parking permits city-wide (many residents see this as a cash-grab by the City); levying fines for the most polluting vehicles (AirCare anyone?); building a charging infrastructure for electric vehicles are areas that need to be examined. And determining how homeowners, renters, and businesses will transition to electric retrofitting without undue hardship are some other areas that need much more work.

Councillors Christine Boyle and Jean Swanson talked about a sense of urgency in rolling out the plan. “We older ones have to listen,” to youth who are fighting for climate change. “There is lots of time for input (on CEAP), but we have to start now,” said Cllr. Swanson. But Cllr. Lisa Dominato, who supports a regional climate emergency plan, said because lower mainland municipalities are interconnected economies, Vancouver should not act in isolation. “We are not an island unto ourselves,” she said.

Cllr. Pete Fry, who has been an active supporter of climate action, tried to ease residents’ fears over concerns relating to CEAP. In Fry’s opinion there is “a lot of misinformation out there” regarding costs and timelines, and he said that most changes would not come into effect for at least a year. Staff will formulate plans for each issue that will require individual approval from Council. And homeowners and businesses, he added, will not have to replace natural gas stoves, fireplaces, furnaces, and hot water tanks until the appliances reach the end of their life.

Council heard from more than 70 speakers on the CEAP, most of whom called on Council to support the 371-page plan in its entirety. Others, including business owners concerned about tolls on cars entering the downtown core, said mobility fees would spell disaster for shops and businesses that are already struggling to stay open during the pandemic. Cllr. Sarah Kirby-Yung questioned staff on the legality of implementing mobility fees, which Mayor Stewart said earlier in the week were not within Vancouver’s legal jurisdiction to decide. City Manager Sadhu Johnston, however, said there were ways for the City to implement charges without requiring approval from the province — details requiring further review.

New fees intended to be charged on vehicles driving into the Vancouver Metro Core apply to the area shown in the map below. The area includes the entire downtown peninsula and the Central Broadway corridor, bounded by 16th Avenue to the south, Burrard Street to the west, and Clark Drive to the east. Driving to and from the North Shore via the Lions Gate Bridge would also be affected.

Graphic: City of Vancouver

Some speakers were concerned that the minimum parking requirements in new developments gives huge financial advantages to developers (even small single lots can have unlimited number of units with no parking requirements). Westbank’s 161-unit Alma and Broadway tower, for example, has 161 units and only 27 underground parking spaces.

Councillors Adriane Carr and Christine Boyle were the most forceful advocates in pushing the CEAP through. “Every piece of the plan is needed to meet our targets,” said Boyle. NPA Cllr. Colleen Hardwick, however, wondered about the timing of the plan, when the city is in the midst of both an affordability and health crisis, and residents are facing a 12 per cent property tax increase next year.

Several amendments to the original motion were proposed with some failing and others passing. Voting in favour of mobility pricing were Mayor Kennedy Stewart, OneCity Cllr. Christine Boyle, Green Party councillors Adriane Carr and Pete Fry, COPE Cllr. Jean Swanson, and independent Cllr. Rebecca Bligh; opposing were NPA councillors Melissa De Genova, Sarah Kirby-Yung, Lisa Dominato, and Colleen Hardwick. Cllr. Michael Wiebe, who owns a restaurant in the downtown core, did not make an appearance at the meeting to avoid a conflict.

In the end, Council voted on more than 30 separate staff recommendations. All were approved, but voting was polarized. NPA councillors either abstained or opposed several of the staff recommendations regarding mobility and affordability.

No Comments